GEOG 332 - Analytical Exercise

Agricultural Specialization in the Midwest and Great Plains

For larger versions of photos, click on image.

Introduction

Almost two-thirds of the United States' total area is in some type of

agricultural land use. The land uses and economies of most states in the

Midwest and Great Plains regions are dominated even more so by the combination

of farming, processing of agricultural commodities, or by services and

industries closely linked to agriculture. Regional sports teams and fan

nicknames also reflect the importance of this basic sector of the economy.

Consider the Nebraska Cornhuskers, Wisconsin "Cheeseheads," and Chicago

Bulls. But alas, all is not perfect as at least one state acknowledges

the vulnerability of farming; Minnesota is also known as the "Gopher State."

Almost two-thirds of the United States' total area is in some type of

agricultural land use. The land uses and economies of most states in the

Midwest and Great Plains regions are dominated even more so by the combination

of farming, processing of agricultural commodities, or by services and

industries closely linked to agriculture. Regional sports teams and fan

nicknames also reflect the importance of this basic sector of the economy.

Consider the Nebraska Cornhuskers, Wisconsin "Cheeseheads," and Chicago

Bulls. But alas, all is not perfect as at least one state acknowledges

the vulnerability of farming; Minnesota is also known as the "Gopher State."

Through this exercise you will interpret the dimensions of farming in three counties located in the Midwest and the Great Plains. Each is among the leaders of their respective states in terms of the value of agricultural output. Yet, they are distinguished by sharply different scales of operations and by variations in their types of farm products. Part of our interest lies in understanding differences in the economic health of farming under each type of specialization.

Agriculture has long been a respected practice in the American economy. However, it is a volatile sector whose unpredictable fortunes often lay beyond the control of the individual farmer. The purpose of this exercise is to contrast the three study counties as you explore their operational differences and offer tentative explanations of the factors behind those distinctions. Your attention should be on three sets of guiding factors: environmental conditions, labor commitment, and sources of income, including governmental support.

American Agriculture in the 1990s

Farming regions and individual farmsteads

may be categorized according to their dominant types of output and their

scale of operations. The typical farmer emphasizes either crop cultivation,

livestock production, or some degree of mixed farming. Even within those

divisions one finds alternative production systems. Crop cultivation,

for example, may be sold for cash or used directly as feed for livestock.

Primary cash grains in the Midwest include corn and soybeans,

two of America's most versatile crops. On the Great Plains, however, the

dominant grain crops are wheat, sorghum, flax, and rapeseed, the latter

of which is the principal source of canola oil. The majority of corn and

grain sorghum output in these two regions ends up as livestock feed.

When field corn (feed corn) is cut and chopped in its immature green stage

it is termed silage. Another prominent field crop is alfalfa,

which also finds its way into stock feed.

Farming regions and individual farmsteads

may be categorized according to their dominant types of output and their

scale of operations. The typical farmer emphasizes either crop cultivation,

livestock production, or some degree of mixed farming. Even within those

divisions one finds alternative production systems. Crop cultivation,

for example, may be sold for cash or used directly as feed for livestock.

Primary cash grains in the Midwest include corn and soybeans,

two of America's most versatile crops. On the Great Plains, however, the

dominant grain crops are wheat, sorghum, flax, and rapeseed, the latter

of which is the principal source of canola oil. The majority of corn and

grain sorghum output in these two regions ends up as livestock feed.

When field corn (feed corn) is cut and chopped in its immature green stage

it is termed silage. Another prominent field crop is alfalfa,

which also finds its way into stock feed.

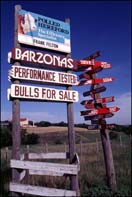

Livestock production

has become much more localized in its geographic distribution and more

closely managed than in the past. No longer does the average farmer maintain

a herd of cattle or several dozen hogs to graze leisurely on the alfalfa

pasture or glean the fields after they have been harvested. Factory-style

feedlots and large-scale hog or chicken farms have replaced

the earlier, more casual livestock operations. The Midwest though is still

known for its hog production in Iowa, western Illinois, and northern Missouri.

Dairying remains a prominent agricultural fixture throughout Wisconsin

and the southern two-thirds of Minnesota. Livestock production is more

likely to be found where soils are thin or of poorer quality for crops,

rainfall amounts are low and unpredictable, and access to regions of demand

is remote. Only on the western margins of the Plains and Nebraska's Sand

Hills region does one find large numbers of beef cattle grazing on so-called

"open range" areas.

Livestock production

has become much more localized in its geographic distribution and more

closely managed than in the past. No longer does the average farmer maintain

a herd of cattle or several dozen hogs to graze leisurely on the alfalfa

pasture or glean the fields after they have been harvested. Factory-style

feedlots and large-scale hog or chicken farms have replaced

the earlier, more casual livestock operations. The Midwest though is still

known for its hog production in Iowa, western Illinois, and northern Missouri.

Dairying remains a prominent agricultural fixture throughout Wisconsin

and the southern two-thirds of Minnesota. Livestock production is more

likely to be found where soils are thin or of poorer quality for crops,

rainfall amounts are low and unpredictable, and access to regions of demand

is remote. Only on the western margins of the Plains and Nebraska's Sand

Hills region does one find large numbers of beef cattle grazing on so-called

"open range" areas.

Farms also may be classified on the basis of the intensity of activity as measured by the amount of labor input required and/or degree of capitalization in farm machinery and other equipment. Intensive agriculture is that which requires large investments of worker time and commitment of capital. Good examples of this type of farming would be dairying, laying chickens, and specialty fruit or vegetable crops. Indicators of intensive agriculture are a typically higher number of days the farmer actually works on the farm, higher value of land and buildings, and a consequent smaller than average acreage on the farm. Extensive agriculture, in contrast, does not need much in the way of either labor input or capitalization. In fact, it often leads to patterns of "sidewalk" or "suitcase" farmers who may own the land but live in a nearby city, working the land only when necessary or else renting the fields to a tenant or part-owner. Wheat farming and cattle ranching fall under the extensive agriculture heading. These types of farms or ranches are typically quite large in size with low capitalization values per acre.

Regardless of the type of product

emphasis, all farmers and ranchers operate within an environment of economic

uncertainty. The vagaries of weather and unknown prices for one's products

four or ten months into the future are perhaps the two most important

unknowns which lead to the farmer's dilemma. What crop or

crops should be planted? When should then be harvested and marketed? Will

consumer demand for red meat continue to fall in favor of chicken? Will

federal and state government price supports for milk and other products

be extended or cut? What do these factors suggest for the prices that

a farmer can expect to receive at the end of the production year?

Regardless of the type of product

emphasis, all farmers and ranchers operate within an environment of economic

uncertainty. The vagaries of weather and unknown prices for one's products

four or ten months into the future are perhaps the two most important

unknowns which lead to the farmer's dilemma. What crop or

crops should be planted? When should then be harvested and marketed? Will

consumer demand for red meat continue to fall in favor of chicken? Will

federal and state government price supports for milk and other products

be extended or cut? What do these factors suggest for the prices that

a farmer can expect to receive at the end of the production year?

Such unknowns create a never-ending series of risks for the farmer. In the face of that climate of risk, it would seem that a wise strategy for the farmer would be to diversify his production activities. Yet, that might require expensive investments in equipment which would sit idle for much of the year or plant a crop which mines the nutrients from the soil or accelerates its erosion. Since the 1960s we have seen a growing tendency for individual farmers and farming regions to become ever more specialized in their emphasis. Even so, more than 40 percent of the American farms in a given year fail to generate a profit. Respect and romanticized images aside, farmers must contend with a prospect of uncertainty and limited return for their hours of effort.

Agricultural Controls and Constraints

What then are the factors

behind local and regional variations in farming practices? At a general

level, the most crucial ones fall under the headings of environmental

conditions, financial controls, and market accessibility. Leading

the list of environmental factors affecting agriculture are precipitation,

growing season, and soil fertility. Financial considerations involve not

only the costs of inputs but also anticipated prices which may be received

from the outputs of production and whether or not government support programs

may help reduce costs or boost revenues. Market access was more important

historically than it is for today's farmers. However, such issues as the

perishability of certain commodities (e.g., strawberries or fluid milk)

and the higher costs of land near cities create generalized rings of declining

farming intensity with increasing distance away from major urban areas.

What then are the factors

behind local and regional variations in farming practices? At a general

level, the most crucial ones fall under the headings of environmental

conditions, financial controls, and market accessibility. Leading

the list of environmental factors affecting agriculture are precipitation,

growing season, and soil fertility. Financial considerations involve not

only the costs of inputs but also anticipated prices which may be received

from the outputs of production and whether or not government support programs

may help reduce costs or boost revenues. Market access was more important

historically than it is for today's farmers. However, such issues as the

perishability of certain commodities (e.g., strawberries or fluid milk)

and the higher costs of land near cities create generalized rings of declining

farming intensity with increasing distance away from major urban areas.

The influences of precipitation amounts, length of growing season, and soil fertility require further explanation. Please refer to your earlier materials from the lectures on weather and climate patterns, and the climate sections in chapters 2, 12 and 13 in your textbook. The "boundary" between the Heartland and the Great Plains generally coincides with a significant climatic boundary--the demarcation zone west of which annual rainfall is less than 20-25 inches. Recurrent drought, pests, and windy conditions are commonplace along this zone, inhibiting the growth of tall row crops such as corn. Even if these conditions are favorable, farmers must endure damage from occasional hail storms and early or late-season snowstorms. Further east, by comparison, the amount of precipitation averages between 30 and 45 inches annually, with a slight maximum during the summer months.

Temperature regimes are also of importance to the farmer's decision-making. Note from the attached "Growing Season" map the south to north gradations in length of the growing season. In central Missouri and Illinois, for example, the average growing season for crops is about 180 days. As one shifts northerly into central Minnesota however, it drops to just 130-140 days.

Glacial outwash and till plains in the Midwest left behind two soil groups highly conducive for agriculture. These are mollisols and alfisols, both of which possess organically rich topsoil layers ranging from dark brown to black in color. (See Soil Map). Mollisols are the richest soil type, having been formed under prairie grasslands. They are very dark in coloration, retain moisture, and yet have a soft, crumbly texture when dry. Hence, they are easily worked for row crops. Alfisols, while still highly productive, are less desirable because they are more acidic and often underlain with a layer of impermeable clay. These developed under forest vegetation, much of which was cleared by the mid-1800s. In western Wisconsin and western Nebraska, one finds yet another soil variety termed entisols. Entisols have poorly developed organic layers and are either very dry or very rocky. They dominate Nebraska's Sand Hills, which act as a sponge, allowing water to penetrate deeply but retaining very little moisture in the top layers that would be accessible to nourish plant life.

Financial considerations must

be taken into account for at least three reasons. First, since all farmers

are, in a sense, competitors with one another, they would want to produce

as much as possible in order to maximize personal revenue. Unfortunately,

a basic principle of economics is that as aggregate supplies increase,

prices fall. Secondly, each farmer is never fully certain of what the

price of a given crop may be at harvest time. Which crop or combination

of crops will yield the highest dollar return per acre? Finally, the costs

of inputs often must be paid "up front," when planting occurs --- outlays

for seed, fertilizer, fuel, and equipment costs all must be carried until

fall harvests. Debt on farm machinery and land looms even larger for many

farmers. Consider that a new dual-wheeled tractor now costs $90,000 -

$110,000 (worth two Mercedes automobiles). Should the farmer "buy the

corn planter or hay baler" or contract out to specialized planting or

harvesting services?

Financial considerations must

be taken into account for at least three reasons. First, since all farmers

are, in a sense, competitors with one another, they would want to produce

as much as possible in order to maximize personal revenue. Unfortunately,

a basic principle of economics is that as aggregate supplies increase,

prices fall. Secondly, each farmer is never fully certain of what the

price of a given crop may be at harvest time. Which crop or combination

of crops will yield the highest dollar return per acre? Finally, the costs

of inputs often must be paid "up front," when planting occurs --- outlays

for seed, fertilizer, fuel, and equipment costs all must be carried until

fall harvests. Debt on farm machinery and land looms even larger for many

farmers. Consider that a new dual-wheeled tractor now costs $90,000 -

$110,000 (worth two Mercedes automobiles). Should the farmer "buy the

corn planter or hay baler" or contract out to specialized planting or

harvesting services?

From the above commentary it is clear that farmers must contend with environmental risks and economic uncertainties, which are often intertwined in complex ways. This background will prove necessary to aiding your interpretation of the farming patterns summarized on the attached tables. (You should re-read the above sections as you work with the individual questions.)

Instructions and Detailed Questions

Submit your responses to the following questions in the form of a brief report entitled, "Agricultural Specialization in the Midwest and Great Plains." That typewritten packet does not need to repeat the detailed questions. A simple numbering of your responses will be adequate. Some may be answered with just a few numbers or a brief phrase. Others will require a paragraph or two of explanations. Do not submit the original data set or these instructions.

After carefully reviewing the tables and maps, please answer the following:

1. What labels would you use to classify each of the three farming counties? What indicators and evidence did you use to make such a categorization? (Three paragraphs maximum)

2. Discuss the role of the controlling environmental factors which explain the variations in cropping and livestock practices among the three study areas. (Three paragraphs maximum)

3. Examine the financial data for these counties. For each one, calculate the

a. average capitalization per farm acre (value of land, buildings and equipment)b. gross sales per farm acre

c. net rate of return (profit) per acre

Display your results in a concise table.

4. Which of the counties contains the most diversified farming practice? How does that diversification relate to financial health? Is risk minimized by diversifying one's activities? (Two paragraphs maximum)

5. Explain how the type of crop or livestock emphasis may affect the necessity for (or the ability to) work off the farm in order to make a decent livelihood. In addition, how might the type of farming specialization impact the extent to which the region is worked by full-owners of the farm land or are either part-owners or renters? (One paragraph)

6. What is happening with government support payments to farmers? How does the distribution of aid relate to the patterns of need or risk? (One paragraph)

7. Respond to the following scenario: Assume that your grandmother recently died and in her will gave you the rights to a 1000 acre farm in each of those counties. However, you must operate the farm for at least three years to gain full ownership. Which farming region(s) would you choose? From the evidence provided, what factors determined your choice? What additional factors not covered by the data set might you consider in making such a tough decision? (Two paragraphs maximum)

Submission Requirements

Please submit your typewritten exercise packet entitled, "Agricultural Specialization in the Midwest and Great Plains," by the due date in your syllabus. Be sure that it also indicates your name. Please, no special covers or binders! Late papers are subject to grade penalties; they will be worth no more than 50 percent of the maximum available points.

Last Modified 10/22/24